Archive for September, 2020

STAR TREK Modeling: A Brief History of the Shuttlecraft Galileo Pt.2

In part 2 of Gary Kerr’s article on the background of the Galileo shuttle, he explores the construction of the miniature and set mockups. Let’s dig in…

A Brief History of the Shuttlecraft Galileo Pt.2 By Gary Kerr

The 22-Footer Takes Shape

Once the Galileo’s final design had been hashed out, construction began in earnest at Gene Winfield’s shop in Phoenix. The target date for completion of the interior set was September 6, 1966, with a target date of September 12 for the exterior prop.

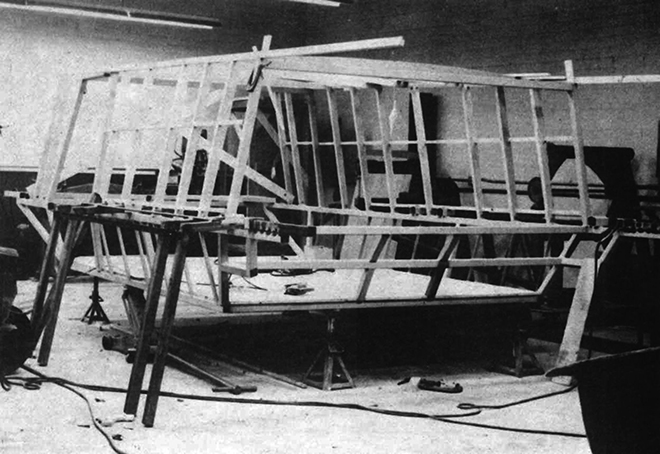

The Galileo mock-up was essentially a sturdy metal skeleton sheathed in wood. The lower half of the prop’s skeleton was made from welded 2” square steel tubing, while the upper half was framed in wood.

A Masonite skin was applied over the skeleton, and fiberglass cloth covered the Masonite. The internal floor was made from a sheet of plywood. To avoid unwelcome reflections in the front windows, they had no glass. Instead, simulated window shutters, consisting of a sheet of Masonite backed by a wooden frame, were inset into the window openings. Curved fins along the upper and lower edges of the hull were made from sheet metal. A bulky metal framework inside the shuttle allowed a technician to operate the 3-piece side door.

The warp nacelle/wing assemblies were designed so they could be removed for transportation or storage. The nacelles, themselves, were made from 18” diameter steel casings made for oil wells, with square steel tubing providing internal strength for the pylons, wings, and connectors that plugged into the hull.

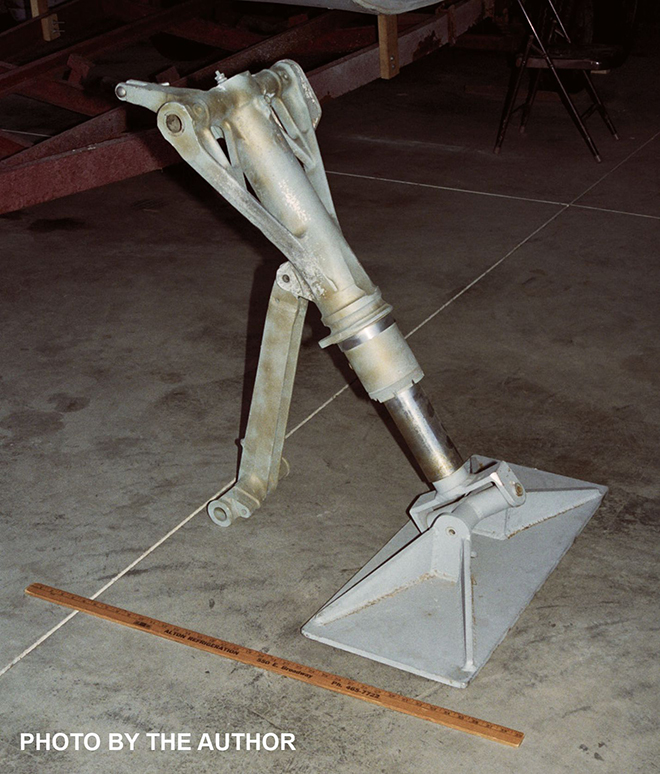

The aft landing strut was salvaged from the landing gear of a scrapped aircraft. The identity of this aircraft has remained a mystery for years. We have the serial number that’s stamped on the landing gear, but this is of limited help since most of the aircraft companies’ old records have been disposed of. The leading contender for the mystery aircraft thus far is the F-106 Delta Dart.

Details, Details…

The intended purpose of a pair of 5.75” by 13”openings, located at the shuttlecraft’s bow, just under the chine, has been a mystery for years. They’ve usually been portrayed as vents in toys and in blueprints drawn by fans, but in every hi-res photo from the 1960s that I examined, they appeared to be nothing more than open holes in the bow. While I was designing Polar Lights’ Galileo kit in 2013, I decided to get the answer straight from the horse’s mouth, so I telephoned Gene Winfield at his shop in Mojave, in the desert north of Los Angeles. Gene explained that the openings were intended for the shuttlecraft’s landing lights, and that the openings would be covered by a pane of glass to make the lights more aerodynamic. He further explained that he had wired the nacelle domes for lighting. The actual lighting would have been installed by union workers at the studio, per the agreement regarding outside vendors, but it appears that budgetary concerns nixed that plan.

Similarly, the impulse deck consisted of a pair of Plexiglas grilles, with the mock-up’s interior being visible through the vents in the grille. During filming, one or more sheets of white material was propped up inside the mock-up to block the view.

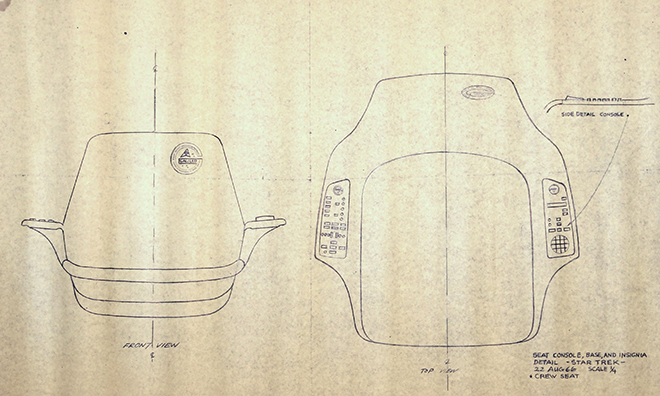

Over a series of phone calls and emails, Mr Winfield explained that most of his papers were still boxed up, following the move to his current location in Mojave. He still had the molds for the Galileo’s fiberglass chairs somewhere, but wasn’t sure where they were stored. He did say that he had a couple old rolls of blueprints laying around, and asked if I’d like to see them. Of course, I said “YES”, and within a week or two, they arrived at my house.

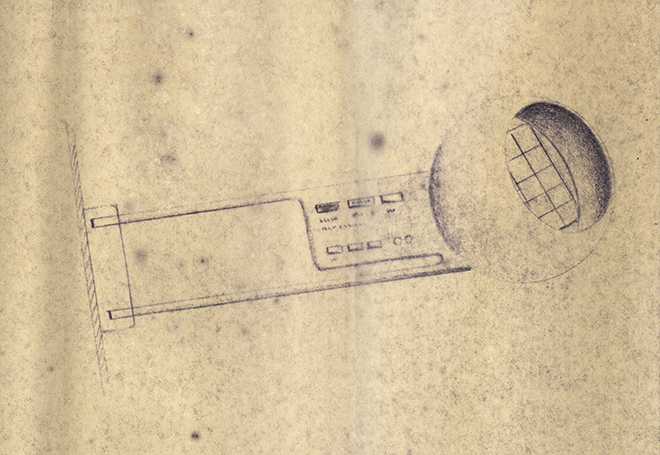

The original plans were extremely yellowed and fragile, and they showed something unexpected: details that Matt Jefferies had designed for the interior set, but which, like the exterior lighting, had never been installed. Included were instrument panels for the swing arms of the two globe-shaped viewers, a Galileo logo for the chairs, and instrument panels for the arms of the chairs (presumably the pilot’s and co-pilot’s).

Next time Gary explores the interior set.

All images courtesy of CBS, except where noted.

TM & (C) 2020 CBS Studios Inc. ARR.

STAR TREK Modeling: A Brief History of the Shuttlecraft Galileo Pt. 1

As the lead developer for our line of sci-fi kits, I can’t be an expert in everything so it is good to know people that “knows people.” One of Round 2’s “go-to” consultants is STAR TREK expert Gary Kerr. If he doesn’t have the answer to any given question he knows who does. He has a lifetime of “side adventures” that have given him close contact with many of the Star Trek filming models and in some cases, our kits are based solely on his exhaustively documented plans of some of the ships he has encountered. Most recently, his plans were used to develop our 1:32 scale Galileo Shuttle model kit. Along the way, he was given the opportunity to write up an article about the Galileo for STAR TREK Magazine published by Titan Publishing. As he wrote, he found that his information overflowed his allotted word count. Neither of us wanted that effort to go to waste so we invited him to publish the overflow on our blog. We’ve chosen to break it up into a series that will be rolled out over the coming weeks. So without further ado. Here is part 1…

A Brief History of the Shuttlecraft Galileo Pt. 1 By Gary Kerr

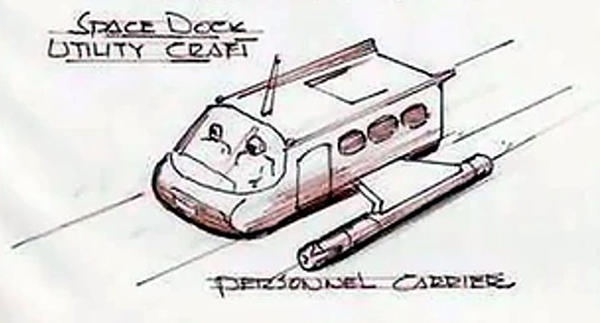

Poor Lieutenant Sulu… slowly freezing to death after a malfunctioning transporter strands him and the rest of the landing party on the increasingly frigid planet Alpha 177. The glitchy transporter beams down heaters, but they are non-functional, and the landing party seems doomed unless Scotty can repair the transporter in time.

Modern viewers of “The Enemy Within” might be forgiven for wondering why the ship simply didn’t send down a shuttlecraft to pick up the landing party. The truth is that even though the Starship Enterprise sported a pair of clamshell hangar bay doors at the end of its engineering hull, it didn’t yet have any shuttlecraft or a hangar to house them in.

This article will examine the history of both the “full-size” Galileo mock-up and the filming miniature. To begin, we should backtrack and examine the origins of Star Trek’s first shuttlecraft.

In the Beginning

As the final design of the Starship Enterprise began to gel in 1964, it became apparent that a starship would probably carry an assortment of smaller craft. Art Director Matt Jefferies added a hangar bay and a pair of clamshell doors to aft end of the ship, but deciding what kind of craft would be housed in the hangar bay was not an easy matter.

One of Jefferies’ initial concepts called for a small, aerodynamic pod that would be light enough to be lowered from the studio ceiling on wires to simulate a landing. This ambitious concept was abandoned as being too costly. Desilu continued to give the construction of shuttlecraft a thumbs-down, which is one of the reasons for Lt Sulu’s predicament in “The Enemy Within.”

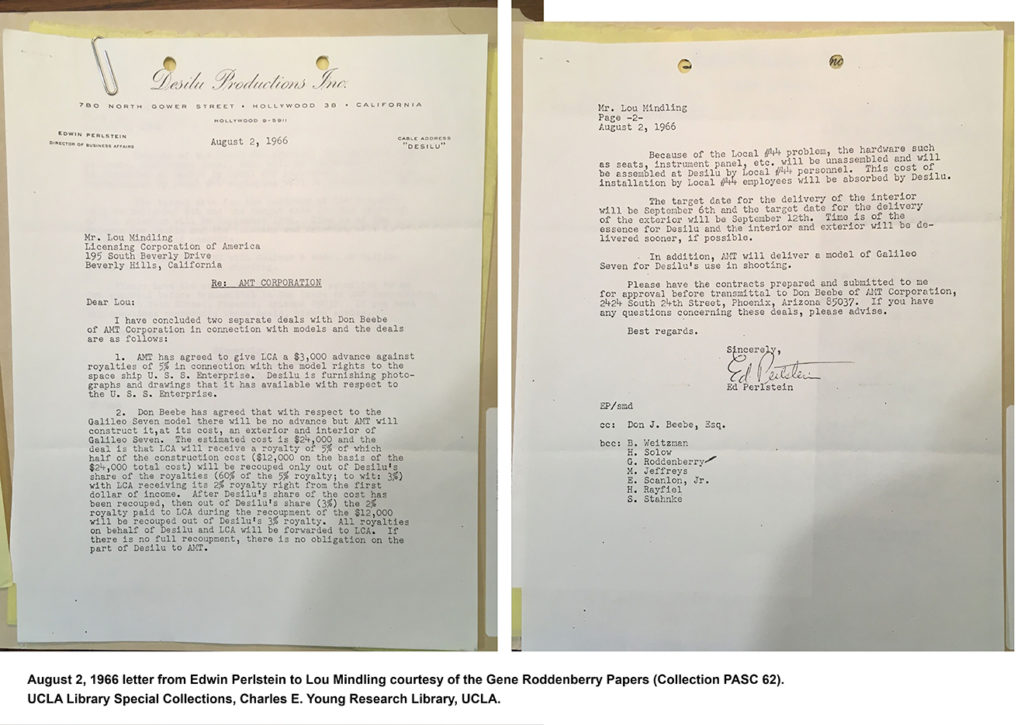

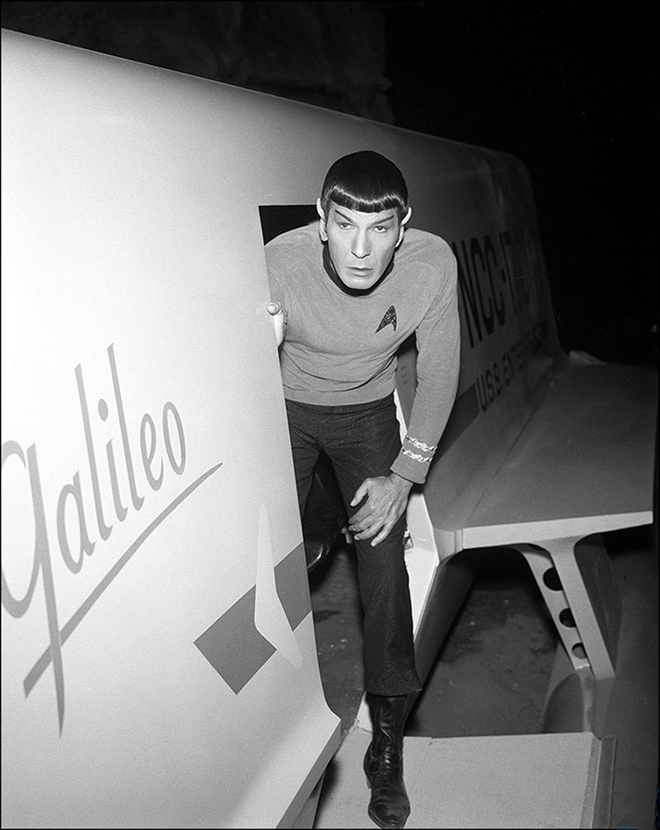

All seemed lost regarding the shuttlecraft situation until August 1, 1966, when Associate Producer Bob Justman informed Gene Roddenberry that Desilu attorney Ed Perlstein had concluded a mutually beneficial deal with the AMT Corporation.

In exchange for rights to produce a plastic kit of the USS Enterprise, AMT agreed to construct both an interior set and exterior mock-up of a shuttlecraft for an estimated $24,000, plus an additional $650 to build a miniature shuttle. The work would be done at AMT’s Speed and Custom Division Shop, in Phoenix, Arizona. Gene Winfield, who was serving as a consultant style designer for AMT’s auto kits, served as production manager.

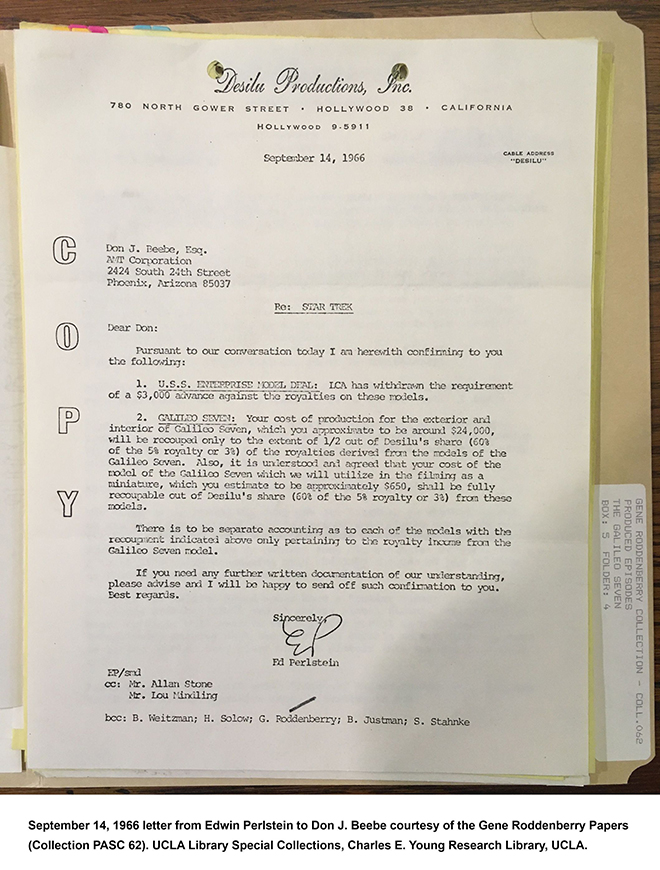

At this point, nailing down the design of the shuttlecraft moved into high gear. Although Matt Jefferies favored a rounded, aerodynamic design for the shuttlecraft, he became the first, but not the last, Star Trek art director to learn that compound curves were a no-no on a television budget and time schedule, and that a shuttlecraft had to be built from sheets or plywood and Masonite. Winfield and Jefferies set about designing a flat-sided shuttle that could be built in the allotted 30 days. The inspiration for the preliminary design seems to have been Jefferies’ 1964 sketch of “Space Dock Utility Craft Personnel Carrier”.

Jefferies and Winfield passed a preliminary design to Thomas Kellogg for further development. Kellogg was an industrial designer, working at the Raymond Loewy Associates design studio in San Francisco. Kellogg worked in some design elements of the studio’s renowned design of the 1963 Studebaker “Avanti” car and created a color rendering of the revamped shuttlecraft.

Jefferies added a pair of warp nacelles to Kellogg’s design, and Winfield’s shop was ready to begin construction of a 22’ prop and a 22” miniature shuttle. Union Local 44 is a professional association of craft persons having specialized skills and talents at Paramount, and the studio’s practice of having outside, probably non-union, vendors supplying props for a TV production would almost certainly cause friction with the union. To avoid problems arising from the studio’s use of outside vendors, the studio and the union arrived at an agreement under which vendors would supply props in an unfinished state, and union craft people would perform the final painting, detailing, and installation of lighting.

Even though the filming miniature and the full-size prop were supposed to represent the same ship, they are not identical. The most obvious difference involves the shape of the hull, with the sides of the 22” miniature being parallel, while the aft end of the 22 ft prop (including the nacelles) flares out slightly wider in back.

Why the difference? To find the answer, we need to jump to the spring of 1992, when I met with Lynne Miller, the owner at the time of the large Galileo prop. The Galileo was located at the Akron-Canton Airport in Ohio, and I spent several hours documenting the shuttle, which was slowly undergoing a restoration.

Lynne revealed that Matt Jefferies had told her that the Galileo was only three-quarter scale. This made perfect sense after I’d climbed inside the shuttle. Being inside the mock-up was akin to crouching inside a very wide minivan. It was certainly a far cry from what we saw on TV! Making “full-size” props at somewhat less than full scale is a common practice in Hollywood. I didn’t realize it at the time, but Matt Jefferies’ brother, John, wrote in his biography of Matt, Beyond the Clouds, that Matt often utilized “illusionary perspective” to create the illusion of distance and makes things appear larger than they actually were. Looking back and seeing that many scenes involving the Galileo were shot at the rear of the prop, I am now convinced that when Jefferies made the rear portion of the 22-footer flare out wider, he was using illusionary perspective to make the three-quarter sized shuttlecraft appear larger.

The use of an undersized prop makes perfect sense: construction costs were less, the prop could be moved more easily around the soundstage, and it took up less precious storage space.

Come back next time as Gary dives into the construction of the miniature and the set pieces.

All images courtesy of CBS, except where noted.

TM & (C) 2020 CBS Studios Inc. ARR.